Often, it seems, people want to avoid drawing hands. Put them behind a leg, or in the grass, or behind a head, or wrapped in fabric - just somewhere, anywhere they don't have to be drawn. Hands are complicated. People have a torso and two legs and two arms and a head. A hand has an arm and a wrist and a palm and four fingers AND a thumb. Not to mention knuckles and fingernails and all those intricate wrinkles and veins and sometimes even fine little hairs.

Like portraits, hands are expressive entities within themselves. How often has a hand carried more gesture and meaning than a face? Second to eyes, they can be used to express so much... if they can be drawn well.

The two drawings above were done for my current figure drawing class. The first was from life, of my own left hand, which was an incredibly awkward way to draw. The second was drawn from a photograph of my hand, and having the photo-reference allowed me to comfortably work over it for a longer time. These were done with charcoal on layout bond, a paper I'm liking more and more the longer I use it.

The big thing is, no matter how much anatomy you go over or how deeply you understand the various tendons and bones of the hand, it's drawn like any other thing. The knowledge of anatomy helps guide your eyes around the various landmarks - we know how the thumb is kind of like a turkey leg, with that big meaty part in the palm, and we know basic arc of the knuckles from one finger to the next. But as the hand twists and turns and moves about, we're forced to sight and measure it like any other object. Thankfully, with all those flat planes and long structures, the hand gives itself over to measurement really rather well.

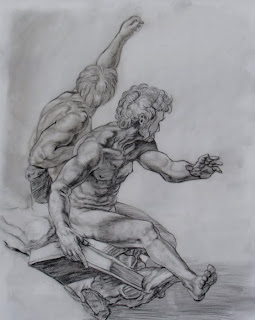

I took photos as I drew my third project for the week, which was to be two hands interacting. I had some fun getting a reference photo of my right hand clipping a clothespin onto my left, giving them some emotion and expression. Like God granting Adam the touch of life, but OW!!! I worked on 18"x24" layout bond with vine charcoal and soft charcoal pencils.

The first step, as always, is the straight-line block-in. This is the most difficult step of any drawing. This is the foundation. Every angle must be sighted and every length must be measured. I used the length of the clothespin to measure everything else. This was all done in vine, which brushes right off the layout bond like it never existed.

Once the basic vine drawing looks accurate and clearly defines the two hands, I got out my sharpened 6B charcoal pencil and went over the outlines, following some of the more subtle curves and details of the forms. I also blocked in the basic shading, very loosely.

Then I ruined it all with a tissue by smearing everything around.

Actually, this is very important when working with charcoal, as this is where we do two things: cover our mistakes, and build up a midtone. By wiping out all the prior work, we also wipe out the plumb lines and various other lines used to build the sketch, and we give the whole drawing a nice layer of light grey.

Time to outline and shade again! Mostly shading this time around, being a bit more careful and detailed in the shadow areas. These are going to be the deepest shadows, the ones that really bring out the forms.

Then we wipe it out AGAIN. Really?? What??? What did that charcoal ever do to you? Well, I want a good midtone. Midtones so often get overlooked, which causes things to look severely lit and lose a lot of "roundness." So I like a nice medium gray. Now the fun begins.

Dudley is already having a lot of fun, see? =D

With the kneaded erasure sculpted into a thin wedge, the light areas and highlights are picked out. Any area that is not *absolutely* white gets smeared with my finger again to tone it back. What we're doing here is letting our five values gradually build up and blend together without a whole lot of effort on our part. When the lighter tones are in, the forms and details really begin to pop out.

The last stage is the longest and most tedious, especially depending on how much time I have and what kind of mood I'm in. Going back with the soft charcoal pencil, the outlines are carefully reintroduced, the shadows are deepened, and the details are brought to life. The tissue and the erasure come back into play, and there's a lot of finger smearing. It's all just plain diligence and a good bit of luck as to how the charcoal will lay and how the drawing when come together.

About 3-4 hours after the sketch was starting, the drawing is all done. I've been going over the smeary background a bit with a shamois, but there's not too much that can be done about it. For an academic drawing, though, it kind of looks appropriate.

In the end, hands are no more a mystery than anything else; they just demand time and attention. And they're so worth it when they come out right, so expressive and such bearers of humanity. So now and then, it's good to lift them out of the grass, or put them out in front of the clothing. It'll be worth it. =)